Lecture 6. Acids, Bases and Solvent Systems.

Hands up all those who would like to see the Bartley Lab adorned with pH 1-14 indicator colours.

An acid (from the Greek oxein then Latin acidus/acére meaning sour) is a

chemical substance whose aqueous solutions were characterized by a sour taste,

the ability to turn blue litmus red, and the ability to react with bases and

certain metals (like calcium) to form salts. Aqueous solutions of acids have a

pH smaller than 7. The lower the pH, the higher the acidity and thus the

higher the concentration of hydrogen ions in the solution (using the Arrhenius

or Brønsted-Lowry definition).

Some notes on acids-bases, pH and the use of

logarithms in calculations are available.

There are a number of common definitions for acids, for example, the

Arrhenius, Brønsted-Lowry, and the

Lewis definition. The Arrhenius definition

defines acids as substances which increase the concentration of hydrogen ions

(H+), when dissolved in water. The Brønsted-Lowry definition

is an expansion of this and defines an acid as a substance which can act as

an H+ donor. By this definition, any compound which can be easily

deprotonated can be considered an acid. Examples include alcohols and

amines which contain O-H or N-H fragments. A Lewis acid is a substance which

can accept a pair of electrons to form a covalent bond. Examples of Lewis acids

include all metal cations, and electron-deficient molecules such as boron

trifluoride and aluminium trichloride.

Common examples of acids include hydrochloric acid (a solution of hydrogen

chloride gas in water, this is the acid found in the stomach that activates

digestive enzymes), acetic acid (vinegar is a dilute solution, generally under 5%),

sulfuric acid (used in wet-cell car batteries), and tartaric acid (a solid

used in baking). As these examples show, acids can be solutions or pure

substances, and can be derived from solids, liquids, or gases.

HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) ⇄ NaCl + H2O

HOAc(aq) + NaOH(aq) ⇄ NaOAc + H2O

H2SO4(aq) + 2NaOH(aq) ⇄ Na2SO4 + 2H2O

HO2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2H(aq) + 2NaOH(aq) ⇄ Na2Tartrate + 2H2O

The "modern" concept of a base in chemistry, stems from

Guillaume-François Rouelle

who in 1754 suggested that a base was a substance which reacted with acids

"by giving it a concrete base or solid form" (as a salt). In addition they gave

aqueous solutions which were characterized as slippery to the touch, tasted

bitter, changed the colour of indicators (e.g., turned red litmus paper blue),

and promoted certain chemical reactions (base catalysis). Examples of bases

are the hydroxides of the alkali and alkaline earth metals

(NaOH, Ca(OH)2, etc.).

For a substance to be classified as an Arrhenius base, it must produce

hydroxide ions in solution. In order to do so, Arrhenius believed the base

must contain hydroxide in the formula. This made the Arrhenius model limited,

as it did not readily explain the basic properties of aqueous solutions of

ammonia (NH3.aq, often written as NH4OH to better fit

the Arrhenius model) or its organic derivatives (amines). In the more general

Brønsted-Lowry acid-base theory, a base is a substance that can accept

hydrogen ions (H+). In the Lewis model, a base is an electron pair donor.

Oxides and Hydroxides

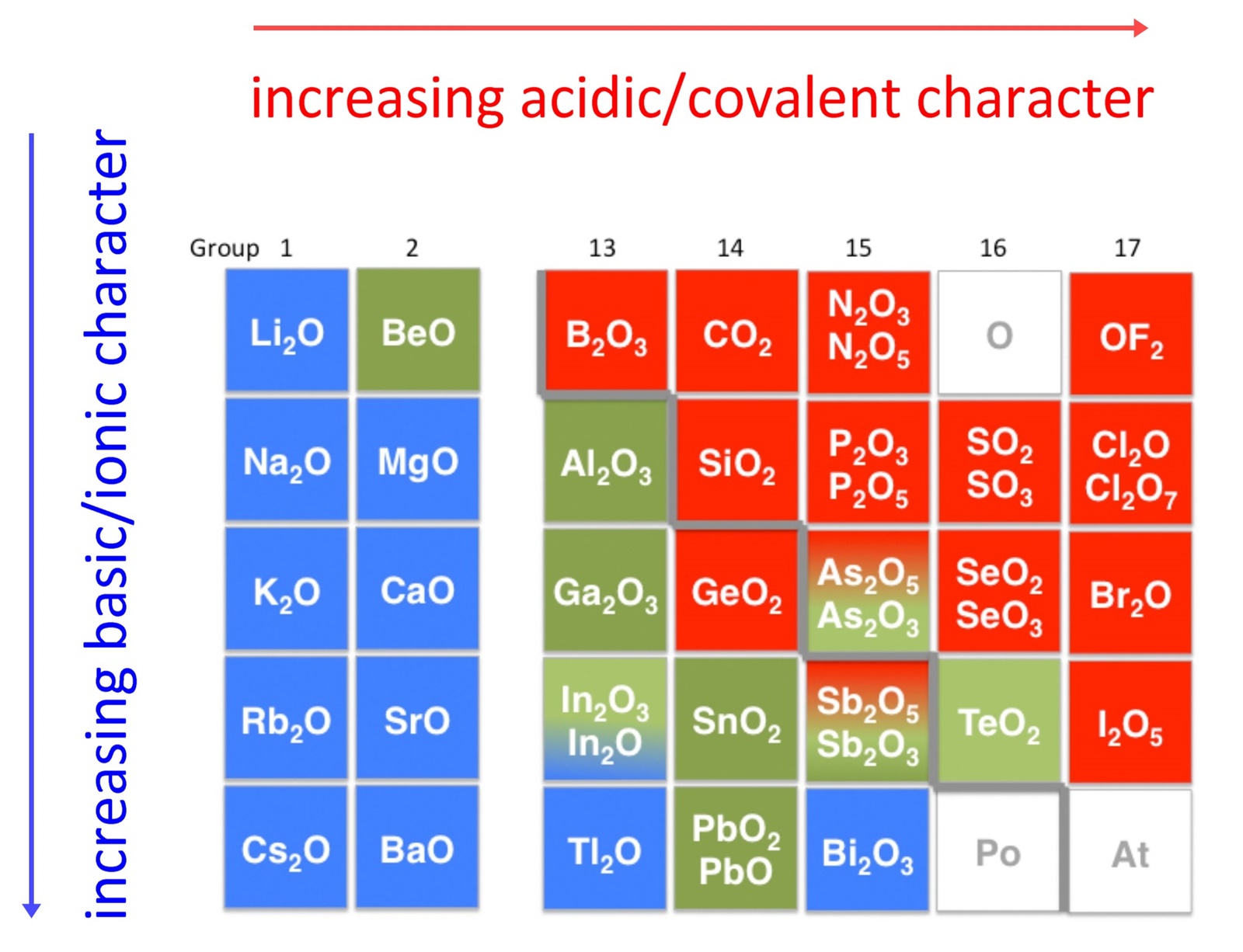

An early classification of substances arose from the differences observed in

their solubility in acidic and basic solutions. This led to the classification

of oxides and hydroxides as being either acidic or basic.

Acidic oxides or hydroxides either reacted with water to produce an acidic

solution or were soluble in aqueous base.

Basic oxides and hydroxides either reacted with water to produce a basic

solution or readily dissolved in aqueous acids. The diagram below shows

there is strong correlation between the acidic or basic character of oxides

(ExOy) and the position of the element, E, in the periodic

table.

Oxides of metallic elements are generally basic oxides, and oxides of

nonmetallic elements acidic oxides. Take for example, the reactions with water

of calcium oxide, a metallic oxide, and carbon dioxide, a nonmetallic oxide:

CaO(s) + H2O(l) → Ca(OH)2

CO2(g) + H2O(l) → H2CO3(aq)

Calcium oxide reacts with water to produce a basic solution of calcium hydroxide,

whereas carbon dioxide reacts with water to produce a solution of

carbonic acid.

There is a gradual transition from basic oxides to acidic oxides from the

lower left to the upper right in the periodic table.

Basicity of the oxides increase with increasing atomic number down a group:

BeO < MgO < CaO < SrO < BaO

Note as well that acidity increases with increasing oxidation state of the element:

MnO < Mn2O3 < MnO2 < Mn2O7

in keeping with the increase in covalency.

Oxides of intermediate character, called amphoteric oxides, are

located along the diagonal line between the two extremes.

Amphoteric species are molecules or ions that can react as an acid as well

as a base. The word has Greek origins, amphoteroi

(άμφότεροι) meaning "both".

Many metals (such as copper, zinc, tin, lead, aluminium, and beryllium)

form amphoteric oxides or hydroxides. Amphoterism depends on the oxidation

state of the oxide.

For example, zinc oxide (ZnO) reacts with both acids and with bases:

In acid: ZnO + 2H+ → Zn2+ + H2O

In base: ZnO + 2OH- + H2O→ [Zn(OH)4]2-

This reactivity can be used to separate different cations, such as zinc(II),

which dissolves in base, from manganese(II), which does not dissolve in base.

Aluminium hydroxide is another amphoteric species:

As a base (neutralizing an acid): Al(OH)3 + 3HCl → AlCl3 + 3H2O

As an acid (neutralizing a base): Al(OH)3 + NaOH → Na[Al(OH)4]

Acid-Base theories and concepts

Arrhenius acids and bases

Although the term proton is often used for H+, this should

really be reserved for H (protium) not D (deuterium) or T (tritium). The more

general term,

hydron

covers all isotopes of hydrogen.

The Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius

attributed the properties of acidity to hydrogen ions (H+) in 1884.

An Arrhenius acid is a substance that, when added to water, increases the

concentration of H+ ions in the water. Note that chemists often write H+(aq)

and refer to the hydrogen ion when describing acid-base reactions, but the free

hydrogen nucleus does not exist alone in water, it exists in a hydrated

form which for simplicity is often written as the hydronium (hydroxonium) ion,

H3O+. Thus, an Arrhenius acid can also be described as a substance

that increases the concentration of hydronium ions when added to water.

This definition stems from the

equilibrium dissociation (self-ionization) of water into hydronium

and hydroxide (OH-) ions:

H2O(l) + H2O(l) ⇌

H3O+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Kw is defined as [H+][OH-] and the value of

Kw varies with temperature, as shown in the table below where at 25 °C

Kw is approximately 1.0*10-14, i.e. pKw= 14.

| Water temperature |

Kw / 10-14 |

pKw

|

| 0 °C |

0.112 |

14.95 |

| 25 °C |

1.023 |

13.99 |

| 50 °C |

5.495 |

13.26 |

| 75 °C |

19.95 |

12.70 |

| 100 °C |

56.23 |

12.25 |

In pure water the majority of molecules are H2O, but the molecules are

constantly dissociating and re-associating, and at any time a small number

of the molecules (about 1 in 107) are hydronium and an equal number

are hydroxide. Because the numbers are equal, pure water is neutral

(not acidic or basic) and has an electrical conductivity of

5.5 microSiemen, μS m-1. For comparison, sea water's conductivity

is about one million times higher, 5 S m-1.

An Arrhenius base, on the other hand, is a substance which increases the

concentration of hydroxide ions when dissolved in water, hence decreasing

the concentration of hydronium ions.

To qualify as an Arrhenius acid, upon the introduction to water, the chemical

must either cause, directly or otherwise:

- an increase in the aqueous hydronium concentration, or

- a decrease in the aqueous hydroxide concentration.

Conversely, to qualify as an Arrhenius base, upon the introduction to water,

the chemical must either cause, directly or otherwise:

- a decrease in the aqueous hydronium concentration, or

- an increase in the aqueous hydroxide concentration.

The definition is expressed in terms of an equilibrium expression:

acid + base ⇌ conjugate base + conjugate acid.

With an acid, HA, the equation can be written symbolically as:

HA + B ⇌ A- + HB+

The equilibrium sign, ⇌, is used because the reaction

can occur in both forward and backward directions. The acid, HA, can lose a

hydron to become its conjugate base, A-. The base, B, can accept a hydron to

become its conjugate acid, HB+. Most acid-base reactions are fast so that the

components of the reaction are usually in dynamic equilibrium with each other.

While the Arrhenius concept is useful for describing many reactions, it has

limitations. In 1923, chemists

Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and

Thomas Martin Lowry independently recognized that acid-base reactions

involve the transfer of a hydron. A Brønsted-Lowry acid (or simply

Brønsted acid) is a species that donates a hydron to a

Brønsted-Lowry base. The Brønsted-Lowry acid-base theory has several

advantages over the Arrhenius theory. Consider the following reactions of

acetic acid (CH3COOH):

CH3COOH + H2O ⇌ CH3COO- + H3O+

CH3COOH + NH3 ⇌ CH3COO- + NH4+

Both theories easily describe the first reaction: CH3COOH acts as an Arrhenius

acid because it acts as a source of H3O+ when dissolved in water, and it

acts as a Brønsted acid by donating a hydron to water. In the second

example CH3COOH undergoes the same transformation, in this case donating a

hydron to ammonia (NH3), but it cannot be described using the Arrhenius

definition of an acid because the reaction does not produce hydronium ions.

A third concept was proposed in 1923 by

Gilbert N. Lewis

which includes reactions with acid-base characteristics that do not involve

a hydron transfer. A Lewis acid is a species that reacts with a Lewis base to

form a Lewis adduct. The Lewis acid accepts a pair of electrons

from another species; in other words, it is an electron pair acceptor.

Brønsted acid-base reactions involve hydron transfer reactions while Lewis

acid-base reactions involve electron pair transfers. All Brønsted acids

are Lewis acids, but not all Lewis acids are Brønsted acids.

BF3 + F- ⇌ BF4-

NH3 + H+ ⇌ NH4+

In the first example BF3 is a Lewis acid since it accepts

an electron pair from the fluoride ion. This reaction cannot be described

in terms of the Brønsted theory because there is no hydron transfer. The

second reaction can be described using either theory. A hydron is transferred

from an unspecified Brønsted acid to ammonia, a Brønsted base;

alternatively, ammonia acts as a Lewis base and transfers a lone pair of

electrons to form a bond with a hydrogen ion.

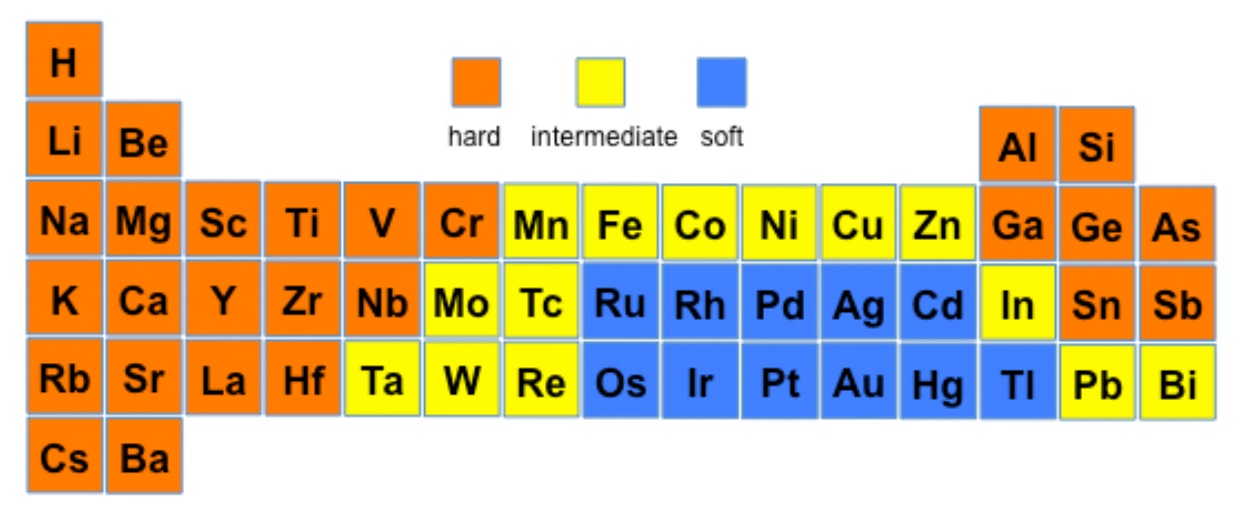

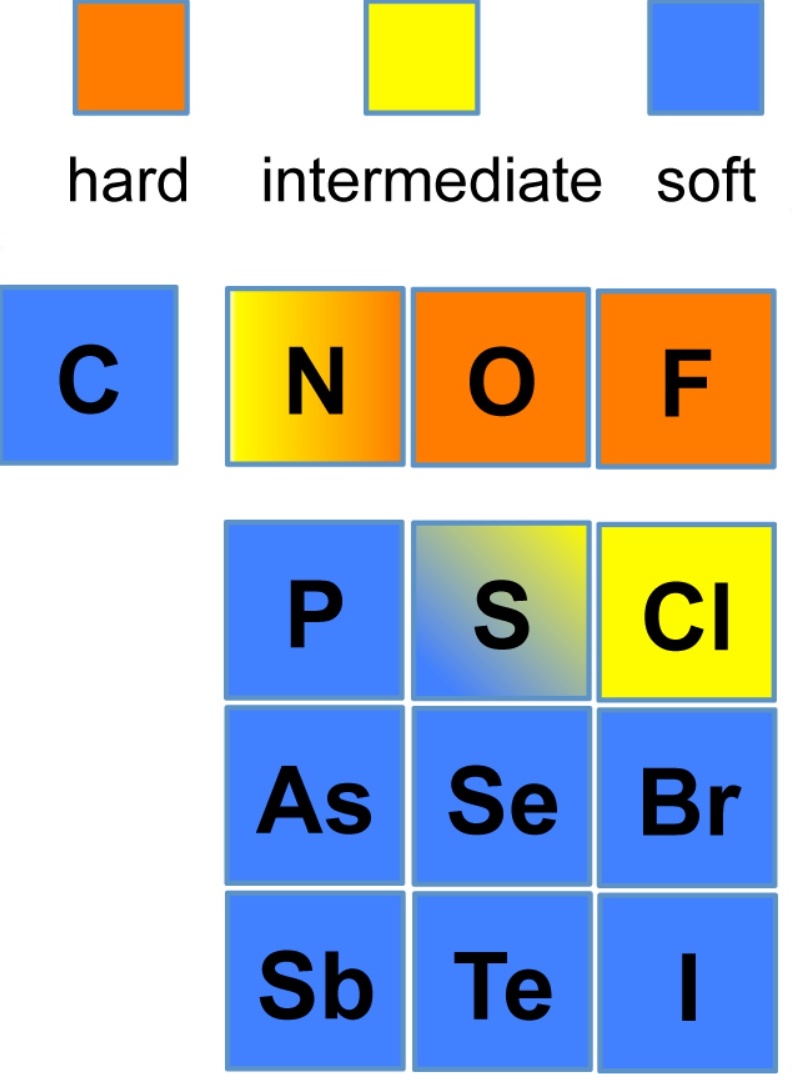

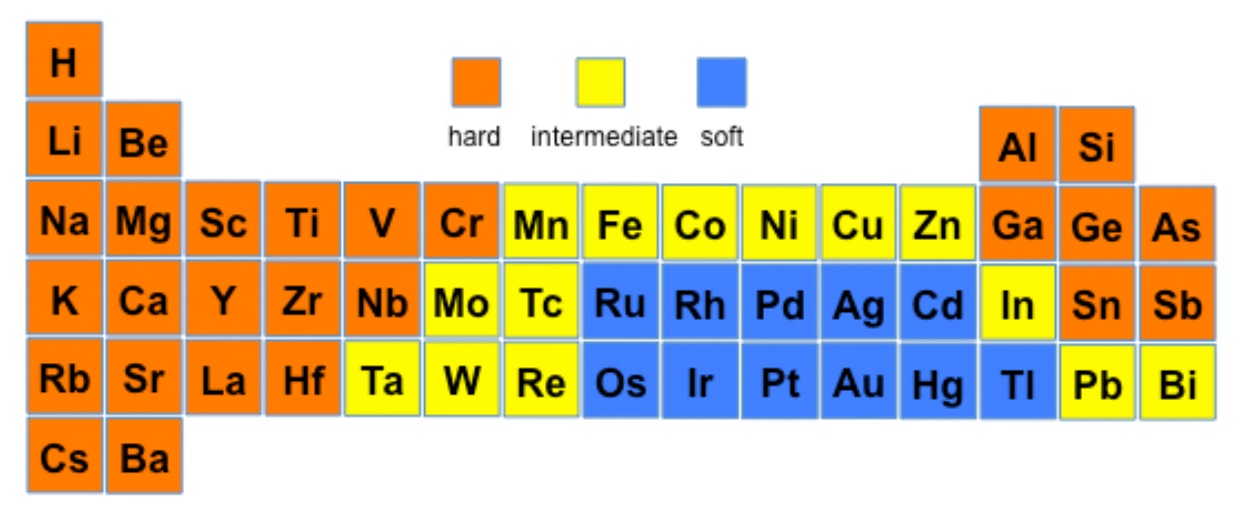

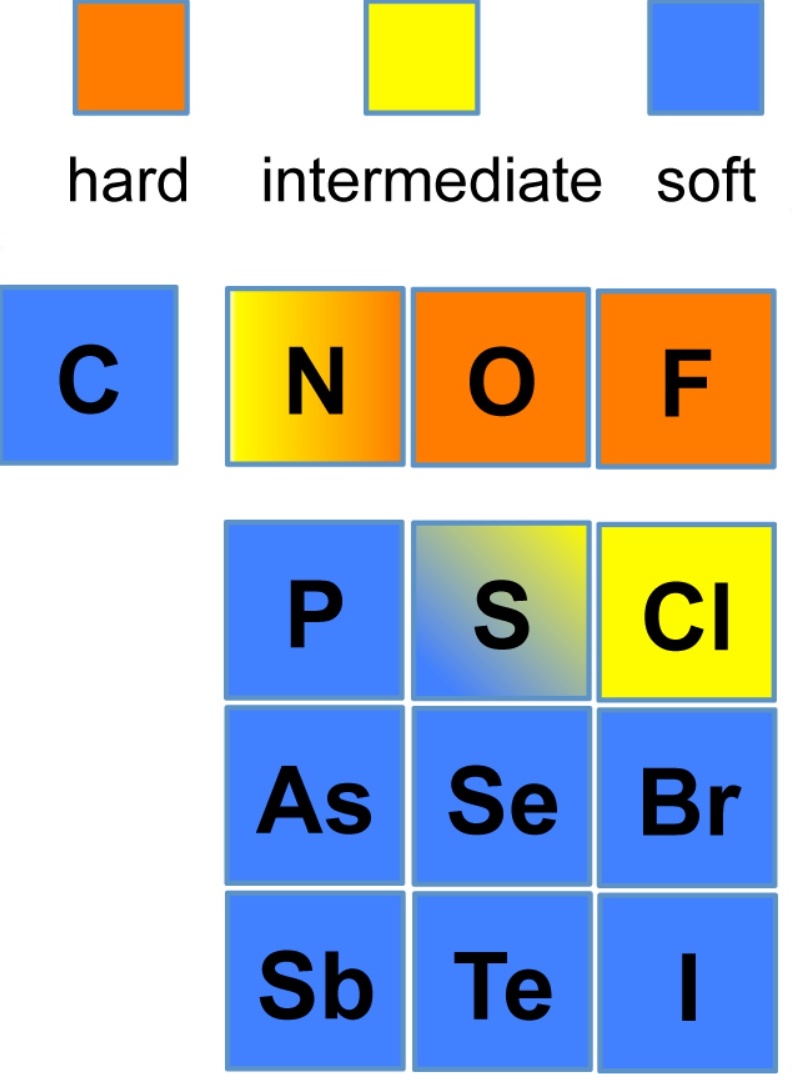

This theory proposes that soft acids react faster and form stronger

bonds with soft bases, whereas hard acids react faster and form stronger bonds

with hard bases, all other factors being equal. The classification

in the original work was largely based on equilibrium constants for the reaction

of two Lewis bases competing for a Lewis acid.

Hard acids and hard bases tend to have the following characteristics:

- small atomic/ionic radius

- high oxidation state

- low polarizability

- high electronegativity (bases)

Examples of hard acids are: H+, light alkali ions

(Li through K are considered to have small ionic radii), Ti4+,

Cr3+, Cr6+, BF3. Examples of

hard bases are: OH-, F-, Cl-,

NH3, CH3COO-, CO32-.

The affinity of hard acids and hard bases for each other is mainly

ionic in nature.

Soft acids and soft bases tend to have the following characteristics:

- large atomic/ionic radius

- low or zero oxidation state bonding

- high polarizability

- low electronegativity

Examples of soft acids are: CH3Hg+,

Pt2+, Pd2+, Ag+, Au+, Hg2+,

Hg22+, Cd2+, BH3.

Examples of soft bases are: H-, R3P,

SCN-, I-.

The affinity of soft acids and bases for each other is mainly

covalent in nature.

HSAB acids and bases

This provides a qualitative approach to looking at the reactions of metal ions

with various ligands since, from the diagram above, it is expected that whereas

Al(III) and Ti(III) would prefer to react with O-species over S-species,

the reverse would be predicted for Hg(II).

This acid-base theory was a revival of the oxygen theory of acids and bases,

proposed by German chemist

Hermann Lux in 1939

and further improved by

Håkon Flood

circa 1947. It is still used in modern geochemistry and for the

electrochemistry of molten salts. This definition describes an acid as an

oxide ion (O2-) acceptor and a base as an oxide ion donor. For example:

MgO (base) + CO2 (acid) ⇌ MgCO3

CaO (base) + SiO2 (acid) ⇌ CaSiO3

NO3- (base) + S2O72-

(acid) ⇌ NO2+ + 2 SO42-

Mikhail Usanovich developed a general theory that does not restrict acidity

to hydrogen-containing compounds, and his approach, published in 1938,

was even more general than the Lewis theory. Usanovich's theory can be summarized

as defining an acid as anything that accepts negative species, anions or electrons

or donates positive ones, cations, and a base as the reverse. This definition

could even be applied to the concept of redox reactions (oxidation-reduction)

as a special case of acid-base reactions.

Some examples of Usanovich acid-base reactions include:

Na2O (base) + SO3 (acid) → 2Na+ +

SO42- (species exchanged: anion O2- )

3(NH4)2S (base) + Sb2S5 (acid)

→ 6NH4+ + 2SbS43-

(species exchanged: anion S2- )

2Na (base) + Cl2 (acid) → 2Na+ + 2Cl- (species exchanged: electron)

A comparison of the above definitions of Acids and Bases shows that the

Usanovich concept encompasses all of the others but some feel that because of

this it is too general to be useful.

The hydron (a completely free or "naked" hydrogen atomic nucleus) is far too

reactive to exist in isolation and readily hydrates in aqueous solution.

The simplest hydrated form of the hydrogen cation, the hydronium (hydroxonium)

ion H3O+ (aq), is a key object of Arrhenius' definition

of acid. Other "simple" hydrated forms include the

Zundel cation

H5O2+ which is formed from a hydron

and two water molecules, and the

Eigen

cation H9O4+, formed from

a hydronium ion and three water molecules. The hydron itself is crucial in the

more general Brønsted-Lowry acid-base theory, which extends the concept

of acid-base chemistry beyond aqueous solutions. Both of these complexes

represent ideal structures in a more general hydrogen bonded network defect.

A freezing-point depression study determined that the mean hydration ion

in cold water is on average approximately

H3O+(H2O)6: where each hydronium

ion is solvated by 6 water molecules.

Some hydration structures are quite large: the

H3O+.20H2O magic ion number structure

(called magic because of its increased stability with respect to hydration

structures involving a comparable number of water molecules).

hydronium ion (H3O+)

|

Zundel cation (H5O2+)

|

Eigen cation (H9O4+)

|

extended hydronium ion (H3O+.20H2O)

|

H vibrations

simuulation by H. Rzepa

|

In 1806

Theodor Grotthuss proposed a theory of water conductivity.

He envisioned the electrolytic reaction as a sort of "bucket line" where

each oxygen atom simultaneously passes and receives a single hydrogen atom.

It was an astonishing theory to propose at the time, since the water molecule

was thought to be OH not H2O and the existence of ions was not

fully understood. The theory became known as the

Grotthuss mechanism.

The transport mechanism is now thought to involve the inter-conversion between

the Eigen and Zundel solvation structures, Eigen to Zundel to Eigen (E-Z-E).

Everything you

wanted to know about water and more.

Water covers 71% of the Earth's surface and is vital for all known forms of life.

On Earth, 96.5% of the planet's water is found in seas and oceans, 1.7% in

groundwater, 1.7% in glaciers and the ice caps of Antarctica and Greenland,

a small fraction in other large water bodies, and 0.001% in the air as vapour,

clouds (formed from solid and liquid water particles suspended in air), and

precipitation.

Only 2.5% of the Earth's water is freshwater, and 98.8% of that water is in

ice and groundwater. Less than 0.3% of all freshwater is in rivers, lakes,

and the atmosphere, and an even smaller amount of the Earth's freshwater

(0.003%) is contained within biological bodies and manufactured products.

The major chemical and physical properties of water are:

- Water is a liquid at standard temperature and pressure.

It is tasteless and odourless. The intrinsic colour of water and ice is a

very slight blue hue, although both appear colourless in small quantities.

Water vapour is essentially invisible as a gas.

- Water is the only substance occurring naturally in all three phases as

solid, liquid, and gas on the Earth's surface

- Water is transparent in the visible electromagnetic spectrum.

Thus aquatic plants can live in water because sunlight can reach them.

Infrared light is strongly absorbed by the hydrogen-oxygen or OH bonds.

- Since the water molecule is not linear and the oxygen atom has a

higher electronegativity than hydrogen atoms, the oxygen atom carries

a partial negative charge, whereas the hydrogen atoms have partial

positive charges. As a result, water is a polar molecule with an electrical

dipole moment.

- Water can form an unusually large number of intermolecular hydrogen bonds

(four) for a molecule of its size. These factors lead to strong attractive

forces between molecules of water, giving rise to water's high surface tension

and capillary forces. The capillary action refers to the tendency of water

to move up a narrow tube against the force of gravity. This property is relied

upon by all vascular plants, such as trees.

- The boiling point of water (like all other liquids) is dependent on the

barometric pressure. For example, on the top of Mount Everest water boils

at 68 °C, compared to 100 °C at sea level at a similar latitude

(since latitude modifies atmospheric pressure slightly). Conversely,

water deep in the ocean near geothermal vents can reach temperatures

of hundreds of degrees and remain liquid.

- Water has a high specific heat capacity,

4181.3 J kg-1 K-1, as well as a

high heat of vaporization (40.65 kJ mol-1), both result from

the extensive hydrogen bonding between its molecules. These two

unusual properties allow water to moderate Earth's climate by buffering

large fluctuations in temperature.

- Solid ice has a density of 917 kg m-3. The maximum density of

liquid water occurs at 3.98 °C where it is 1000 kg m-3.

- Elements that are more electropositive than hydrogen such as lithium, sodium,

calcium, potassium and caesium displace hydrogen from water, forming hydroxides.

Since hydrogen is a flammable gas, when given off it is dangerous and the reaction

of water with the more electropositive of these elements can be violently

explosive so they are often stored in oil.

Most known pure substances display simple behaviour when they are cooled, they

shrink. Liquids contract as they are cooled because the molecules move slower

and they are less able to overcome the attractive intermolecular forces drawing

them closer to each other. Once the freezing temperature is reached, the

substances solidify, causing them to contract even more because

crystalline solids are usually tightly packed.

Water however water has the anomalous property of becoming less dense

when it is cooled to its solid form, ice.

When liquid water is cooled, it initially contracts as expected,

until a temperature of 3.98 °C is reached (~4 °C). After that, it

expands slightly until it reaches the freezing point, and then when it

freezes, it expands by approximately 9%.

Just above the freezing point, the water molecules begin to locally arrange

into ice-like structures with an extended hydrogen bonded network.

This creates some "openness" in the liquid water,

accounting for the decrease in its density. This is in opposition to the usual

tendency for cooling to increase the density. At 3.98 °C

these opposing tendencies cancel out, producing the density maximum.

Since water expands to occupy a 9% greater volume in the form of ice and is

less dense, it floats on liquid water, as in icebergs. Fortunately this

happens, since in colder climates where water is susceptible to freezing, if it

all turned solid during the winter, it would kill all the life within it.

The extended structure of the water molecule in liquid and solid form

seen in the models below provides the explanation for the variation of density

with temperature.

extended structure of liquid water

|

extended structure of solid ice

|

A solvent (from the Latin solvo-, "I loosen, untie, I solve") is a

substance that dissolves a solute (a chemically different liquid, solid or gas),

resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can be a solid or

a gas. The maximum quantity of solute that can dissolve in a specific volume

of solvent varies with temperature.

Although many inorganic reactions take place in aqueous solution, water is not

always the most suitable solvent; some reagents react violently or decompose in

water (e.g. the alkali metals) and non-polar molecules are often insoluble

in water.

Solvents can be broadly classified into two categories: polar and non-polar.

Generally, the

relative permittivity

(εr, formerly called the dielectric constant) of the

solvent provides a rough measure of a solvent's polarity. This can be thought

of as its ability to insulate charges from each other and acts as a reasonable

predictor of the solvent's ability to dissolve common ionic compounds, such as salts.

The strong polarity of water is indicated, by a relative permittivity of

88 at 0 °C compared to 1 by definition for a vacuum. Solvents with a

relative permittivity of less than 15 are generally considered to be nonpolar.

Coulombic potential energy ∝ q1q2/(4 π ε0 εr r)

A value of 88 can be considered to be a 'high' value and from the expression

for Coulombic electric potential, the force between two point charges

(or two ions) in aqueous solution is considerably reduced compared

with that in a vacuum. Thus a dilute aqueous solution of a salt

is considered to contain well-separated, non-interacting ions.

The polarity, dipole moment, polarizability and hydrogen bonding of a solvent

determines what type of compounds it is able to dissolve and with what other

solvents or liquid compounds it is miscible. Generally, polar solvents

dissolve polar compounds best and non-polar solvents dissolve non-polar

compounds best: "like dissolves like". Strongly polar compounds like sugars

(e.g., sucrose) or ionic compounds, like inorganic salts (e.g., table salt)

dissolve only in very polar solvents like water, while strongly non-polar

compounds like oils or waxes dissolve only in very non-polar organic solvents

like hexane. Similarly, water and hexane (or vinegar and vegetable oil) are

not miscible with each other and will quickly separate into two layers even

after being shaken well.

Solvents with a relative static permittivity greater than 15 (i.e. polar

or polarizable) can be further divided into protic and aprotic. Protic

solvents solvate anions (negatively charged solutes) strongly via hydrogen

bonding. Water is a protic solvent. Aprotic solvents such as acetone or

dichloromethane tend to have large dipole moments (separation of partial

positive and partial negative charges within the same molecule) and solvate

positively charged species via their negative dipole.

Properties Table for some common solvents

| Solvent |

Chemical formula |

Boiling point / °C |

Relative permittivity |

Density / g ml-1 |

Dipole moment / D |

| Non-polar solvents |

| Pentane |

C5H12 |

36 |

1.84 |

0.626 |

0.00 |

| Hexane |

C5H14 |

69 |

1.88 |

0.655 |

0.00 |

| Benzene |

C6H6 |

80 |

2.3 |

0.879 |

0.00 |

| Toluene |

C6H5-CH3 |

111 |

2.38 |

0.867 |

0.36 |

| Chloroform |

CHCl3 |

61 |

4.81 |

1.498 |

1.04 |

| Dichloromethane |

CH2Cl2 |

40 |

9.1 |

1.3266 |

1.60 |

| Polar aprotic solvents |

| Ethyl acetate |

AcO-Et |

77 |

6.02 |

0.894 |

1.78 |

| Acetone |

(CH3)2C=O |

56 |

21 |

0.786 |

2.88 |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) |

(CH3)2NCH(=O) |

153 |

38 |

0.944 |

3.82 |

| Acetonitrile (MeCN) |

CH3-C≡N |

82 |

37.5 |

0.786 |

3.92 |

| Nitromethane |

CH3-NO2 |

100–103 |

35.87 |

1.1371 |

3.56 |

| Propylene carbonate |

C4H6O3 |

240 |

64 |

1.205 |

4.9 |

| Polar protic solvents |

| Formic acid |

H-C(=O)OH |

101 |

58 |

1.21 |

1.41 |

| n-Butanol |

CH3-CH2-CH2-CH2-OH |

118 |

18 |

0.810 |

1.63 |

| n-Propanol |

CH3-CH2-CH2-OH |

97 |

20 |

0.803 |

1.68 |

| Ethanol |

CH3-CH2-OH |

79 |

24.55 |

0.789 |

1.69 |

| Methanol |

CH3-OH |

65 |

33 |

0.791 |

1.70 |

| Acetic acid |

CH3-C(=O)OH |

118 |

6.2 |

1.049 |

1.74 |

| Water |

H-O-H |

100 |

80 |

1.000 |

1.85 |

Acid and Base effects in non-aqueous solvents.

Levelling and differentiating solvents

When a strong acid is dissolved in water, it fully dissociates to form the

hydronium ion (H3O+). For example:

HA + H2O → A- + H3O+ (where "HA" is a

strong acid)

No acid can be stronger than H3O+ in H2O.

Strong acids can be said to be "levelled" in water.

The same argument applies to bases. In water, OH- is the strongest base.

Thus, even though sodium amide (NaNH2) is an exceptional base

(pKa of NH3 ~ 33), in water it is "levelled" and is

only as strong as sodium hydroxide.

In a differentiating solvent, acids dissociate to varying

degrees and thus have different strengths. In a levelling solvent,

acids become completely dissociated and are thus of the same strength.

A weakly basic solvent has less tendency than a strongly basic one to accept

a hydron. Similarly a weak acid has less tendency to donate hydrons than a

strong acid.

All acids tend to become indistinguishable in strength when dissolved in

strongly basic solvents, owing to the greater affinity of strong bases for

hydrons, ("levelling").

A strong acid, such as perchloric acid, exhibits more strongly acidic

properties than a weak acid, such as acetic acid, when dissolved in a

weakly basic solvent, ("differentiation").

For acids, strong bases are levelling solvents, weak bases

are differentiating solvents.

Another classification of solvents is on the basis of hydron interaction:

- Protophilic solvents: Solvents which have greater tendency to accept hydrons, i.e., water, alcohol, liquid ammonia, etc.

- Protogenic solvents: Solvents which have the tendency to produce hydrons, i.e., water, liquid hydrogen chloride, glacial acetic acid, etc.

- Amphiprotic solvents: Solvents which act both as protophilic or protogenic, e.g., water, ammonia, ethyl alcohol, etc.

- Aprotic solvents: Solvents which neither donate nor accept hydrons, e.g., benzene, carbon tetrachloride, carbon disulfide, etc.

HCl acts as an acid in H2O, a stronger acid in NH3,

a weak acid in CH3COOH, neutral in benzene and

a weak base in HF.

Return to the course outline

References

Much of the information in these course notes has been sourced from Wikipedia under

the Creative Commons License.

'Inorganic Chemistry' - C. Housecroft and A.G. Sharpe, Prentice Hall, 4th Ed.,

2012, ISBN13: 978-0273742753, pps 24-27, 43-50, 172-176, 552-558, 299-301, 207-212

'Basic Inorganic Chemistry' - F.A. Cotton, G. Wilkinson and P.L.

Gaus, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 3rd Ed., 1994.

'Introduction to Modern Inorganic Chemistry' - K.M. Mackay, R.A.

Mackay and W. Henderson, International Textbook Company, 5th Ed., 1996.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Return to Chemistry,

UWI-Mona, Home Page

Created and maintained by Prof. Robert J.

Lancashire,

Return to Chemistry,

UWI-Mona, Home Page

Created and maintained by Prof. Robert J.

Lancashire,

The Department of Chemistry, University of the West Indies,

Mona Campus, Kingston 7, Jamaica

Created November 2014. Links checked and/or last

modified 7th March 2015.

URL

http://wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm/courses/CHEM1902/IC10K_MGAcidsBases.html

Return to Chemistry,

UWI-Mona, Home Page

Created and maintained by Prof. Robert J.

Lancashire,

Return to Chemistry,

UWI-Mona, Home Page

Created and maintained by Prof. Robert J.

Lancashire,